Whether you call them crayfish, crawfish, or crawdad, this creature needs protection nationwide to prevent extinction, according to Chris Taylor, Illinois Natural History Survey curator at the University of Illinois. In a recent article published in the journal Hydrobiologia, Taylor and colleagues have outlined possible strategies for conservation practices to protect crayfish from invasive species, habitat changes, and potential overexploitation.

The United States has the richest diversity of crayfish fauna in the world with 394 species and subspecies, and scientists who study crayfish believe that half of the total number of species need some type of conservation attention. Yet only six species are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act.

“There is a big dichotomy between what aquatic biologists think should be protected and what is actually protected by law,” Taylor said. “Crayfishes are a critically important link in energy flow in aquatic ecosystems, as they eat algae and convert it into animal tissue.”

The first crayfish weren’t listed under the Endangered Species Act until the late 1980s. By contrast, many species of mussels and fishes were listed decades earlier.

Once species are listed, the Endangered Species Act requires certain agencies to monitor and maintain protected animals. Consequently, funding is allocated to the study of protected species.

With funding available for studies, several hundred scientists in the United States study mussels, whereas only a handful study crayfish, Taylor said. What’s more, comprehensive conservation strategies and efforts have been implemented for mussels, but only marginally so for crayfishes.

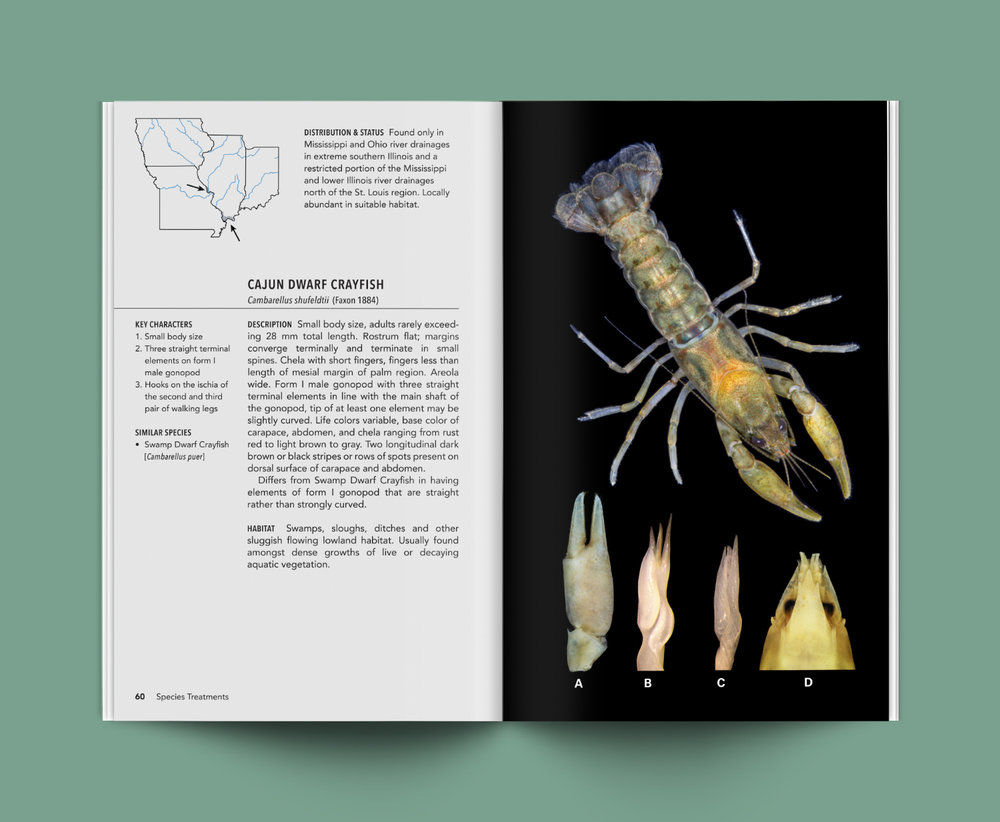

One of the key reasons that crayfishes are at risk is because species often have an extremely narrow range of only one or two river drainages, or in some cases one or two streams. If a stream became polluted from a chemical spill, for example, an entire species of crayfish could be wiped out. Habitat changes from stream channelization or dredging and sedimentation also pose a risk.

Another problem is that invasive crayfish compete with native species for resources.

“The Rusty Crayfish is the poster child for the perils of invasive aquatic species,” Taylor said. “They have been used for fishing bait for a very long time. At the end of a day, fishermen typically leave their live bait in lakes or streams rather than taking them back home or they escape from fishing hooks, and thus the invasives have spread.”

Although overharvesting of crayfish hasn’t been documented, under-monitoring and lax record keeping could potentially lead to exploitation. Not enough attention is paid to harvesting of crayfish, so relatively rare species could be in danger.

Knowledge gaps in understanding the physiology, habitat needs, stress, and evolutionary relationships of crayfish are also a problem.

“We believe that crayfish are susceptible to changes in habitat, invasive crayfishes, and climate, but we don’t know what they can tolerate in terms of chemical or non-chemical stressors,” Taylor said. “That lack of knowledge is a threat in itself.”

In the article in Hydrobiologia, Taylor and colleagues provide some strategies for consideration, including increased attention to crayfish environmental tolerance limits, crayfish harvest and overexploitation, and regulations for preventing the spread of invasive species. Another strategy is to focus on crayfish needs for habitat restoration efforts.

“This paper is a working document, a call for researchers to start thinking about management activities for crayfish species,” Taylor said, “We openly invite those working in crayfish research and conservation to test the plan or suggest alternative strategies. There have been some improvements over time, but there are still gaps in research, policy, and conservation.”

The article, Towards a Cohesive Strategy for the Conservation of the United States’ Diverse and Highly Endemic Crayfish Fauna, is available online.

—-

Media contact: Chris Taylor, 217-244-2153, cataylor@illinois.edu

news@prairie.illinois.edu